Shea trees like this one are under threat due to human activity, putting the livelihoods of millions of women in West Africa at risk.

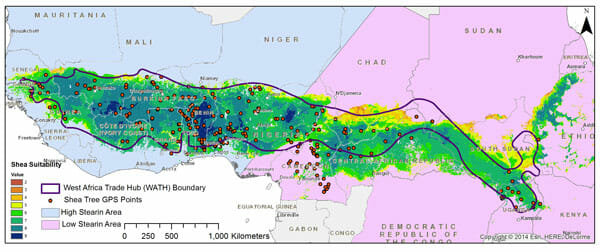

For millions of years, shea trees have grown across Africa – from Senegal to Uganda – within a semi-arid zone known as the Sahel-Savannah. And for thousands of years, people have used shea nuts from the trees to make shea butter, an edible fat that is a part of daily life for millions of Africans and, today, for billions around the world.

But shea trees are under significant stress, says Dr. Peter Lovett, a leading shea ecology expert speaking at the College of Staten Island Wednesday, Oct. 10 in the Campus Center, Room 211 (1C).

The source of that stress? Human beings.

“The modernizing of agriculture, loss of fallows, the use of chemicals in agriculture, and urbanization are having a significant negative impact on the trees,” Dr. Lovett said. “We are losing the opportunity to regenerate the trees naturally and without any tradition of tree planting, the parklands where these trees thrive are highly threatened.”

The loss of shea trees has profound impacts directly on West African women, who depend on shea nuts and butter sales for their livelihoods. Traditionally, women primarily collect and trade shea nuts and make, eat, and sell shea butter. The women trade the shea nuts to companies that make specialty fats that are used primarily in making chocolate candy – every time you eat a Snickers or a Milky Way, you’re eating shea. They also make shea butter as a staple edible oil or fat for local consumption – it’s used in cooking, frying and for moisturizing their skin and hair.

The same shea butter that is used to make confectionery fats also ends up in a wide variety of personal care products on the international market, which is generally how most Americans become aware of shea. The fact that shea butter is edible is not well known, yet refined to food grade it could also be a viable alternative to other oils and fats.

In terms of ecological restoration, “there are various projects around the region, but they’re very small scale projects,” explained Dr. Lovett. “These projects are aimed at generating thousands and planting of trees. But with shea parklands occupying 350 million hectares – over one third of the USA’s land area – we should be thinking of generating and planting hundreds of millions, if not billions of trees across this vast landscape of sub-Saharan Africa.”

Dr. Lovett said he will start his talk by presenting the traditional shea system and then discuss the markets for shea butter, from local food security and consumption to chocolate to cosmetics. Then, he said, he’ll explain “what’s going wrong and potential business opportunities for landscape restoration and market expansion.”