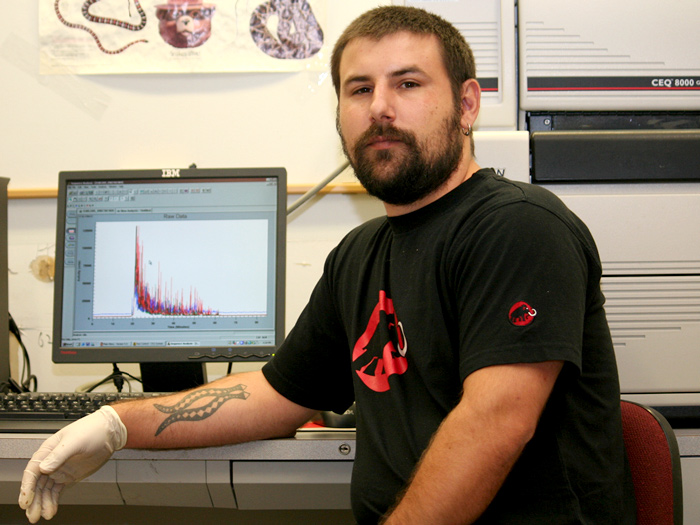

Doctoral candidate Tim Guiher is in his fifth and final year in CSI Biology Professor Frank Burbrink’s lab, hoping to receive his PhD this spring. He has also received a 2009 Doctoral Student Research Grant, adding to the recognition that he received through his selection for a 2008 Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Fund grant from the American Museum of Natural History.

When asked about his research, Guiher begins by discussing the unique environment in Burbrink’s lab. “One of the benefits of working here in this lab is you have one project that you’re kind of focused on for your dissertation but then you’ve got several projects that you can work on simultaneously, either collaboratively with Frank or other collaborators that Frank might be working with, and there have been a lot of different questions that we get to ask here. Secondly, right now, people [who are studying] systematics [the study of the diversification of life on the planet Earth, both past and present, and the relationships among living things through time] kind of go through this transition zone—methodologically and theoretically, so the approaches that we take toward the questions that we ask have really drastically changed since I got here four years ago. So, approaches to the questions that we were asking when we first came in have really evolved along with the field as these new methods have come along. Now, we’re required to constantly learn new methodologies as these new approaches become available. That means new software we have to learn, new theories, and we may address a question one way and six months later say, ‘hey, we’ve got a new method available to us, which allows us to address this from a different point of view, so let’s do this again.’”

Guiher notes that this constantly changing research playing field isn’t frustrating, but “invigorating.” In fact, thanks to the learning curve in the lab, he and his fellow students are taking leadership roles with other scientists. “The nice thing about it is we’ve become very adept at learning these new methodologies very quickly. Within a couple of days, we can go through all the relevant literature, learn the methodologies to the point of where we have people from Yale and Berkeley who have actually come out here to our lab and said, ‘okay, you guys are familiar with these methodologies, now can you teach them to us?’ That’s a great asset for us.”

As for his current research, Guiher explains, “My main focus when I came in was biogeography and historical biogeography of two snakes in the genus of Agkistrodon. Specifically the two snakes I’m working on are the copperhead and the water moccasin or cottonmouth. Currently, there are four species recognized in that genus, two of which are Central American. Prior to 1999 or 2000, the two Central American ones were considered one species. Based on work that is similar to what I am doing it was actually found that these are two species, which is kind of what led me into what I’m doing now. I said, ‘okay, now let’s look at the two North American ones which we can sample much more densely, because they’re North American, and let’s do a similar study and see if there are actually multiple species of these, which is now what we’re finding.”

Now that he has almost completed his doctoral research, what does the future hold for Guiher? “This is the kind of question that keeps me awake every night,” he says with a chuckle. “This next year will really be spent, along with writing up my dissertation, applying for post-docs and jobs and trying to figure out what’s next for me. My hopes are to have a post-doc, probably a two-year position, and then applying for jobs as a professor somewhere in a university—hopefully a university large enough where I can have my own grad students—or a museum as a curator…My main focus is continuing to do research.”

![[video] Newly Formed Partnership with Vietnamese University Celebrated](https://csitoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/ELI-Cultural-Day-080713.jpg)