STATEN ISLAND ADVANCE — Tuesday marks the one-year anniversary of Superstorm Sandy’s devastating attack on our portion of the East Coast. The storm was a wake-up call to the entire New York metropolitan area — but especially to Staten Island, the Rockaways, Breezy Point and other low-lying coastal areas.

STATEN ISLAND ADVANCE — Tuesday marks the one-year anniversary of Superstorm Sandy’s devastating attack on our portion of the East Coast. The storm was a wake-up call to the entire New York metropolitan area — but especially to Staten Island, the Rockaways, Breezy Point and other low-lying coastal areas.

We can only prevent future calamities by learning from the past, and using that knowledge to guide us in the future.

I would like to emphasize the importance of an interdisciplinary approach to formulating a response to natural disasters. Throughout my career, when I have worked on natural disasters, scientists made predictions and no one listened. This is because, for the message to be received, we as scientists need to include politicians, business leaders, social scientists, economists, humanists and community leaders. This “serious conversation” needs to be a team approach, as the frequency and severity of tropical storms are likely to increase.

In June 2012, five months before Sandy, most people did not think of New York as lying within the hurricane belt, although powerful storms have impacted our city before.

In 1932 there was a hurricane of unknown strength with a 15-plus foot surge (based on our analysis of newspaper photos) and in 1938 an unnamed Category 3 hurricane, sometimes referred to as the Long Island Express, that produced a surge in the neighborhood of 20 feet. These storms went somewhat unnoticed, at least on Staten Island, because the surges rolled across undeveloped marshland.

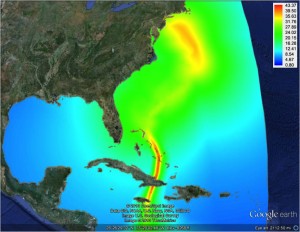

Sandy’s maximal wind speed along actual hurricane’s track. Generated by the CUNY High Performance Computing Center at the College of Staten Island.

UNIQUE STORMS

Each storm is different; strength, eye track, tides and other weather systems all play a factor. The surge starts as a low-pressure bulge in the ocean in the eye of the storm (think of water rising into a vacuum cleaner). Winds pile water on top of the bulge and tide then lifts the water to an even higher level. The New York Metropolitan area sits at a particularly vulnerable area.

The right angle of the shoreline created by the intersection of the New Jersey shore and Long Island and counterclockwise rotation drives wind and water against Staten Island and up New York Harbor. This surge water is then trapped by wind driving water westward along Long Island Sound.

Within the New York metropolitan area, Staten Island is particularly vulnerable. The narrowing passage created by the Long Island and New Jersey shores, in conjunction with a shallowing sea floor ramp, pressurizes the water and focuses it against the South Shore, greatly increasing the surge’s height and intensity.

Rising sea levels only complicate a surge situation, and higher sea levels should be viewed as the new normal. Sea level has been rising at about a foot a century for the past 5,000 years and that rate is likely to increase — maybe to as much as two to five feet per century. This has been masked because we have been developing shore areas faster than the sea level rise. However, this is not sustainable.

Barrier islands, marshes, coastal dune fields, estuaries and bays are nature’s sponges that absorb the energy of a storm surge and store water that mitigates damage and flooding — and, through overdevelopment, we have hardscaped our sponges, leaving these areas extremely vulnerable to flood damage.

FIVE-POINT PLAN

In light of the fact that Sandy was a relatively minor event with a 14-foot storm surge, and there is scientific speculation that the area could encounter surges of 30, and perhaps even 38 feet, I offer a five-point plan to guide the “serious conversation:”

1. Protect our existing dunes, marshes, wetlands and barriers whenever possible.

2. Rebuild and restore coastal dune fields and marshes.

3. Consider rezoning high-risk areas for day use and recreational purposes. Even within the flood zone, some areas are more vulnerable than others.

4. Consider appropriate use of seawalls, floodgates, and other engineering solutions, and understand that engineering solutions almost always protect one area at the expense of another.

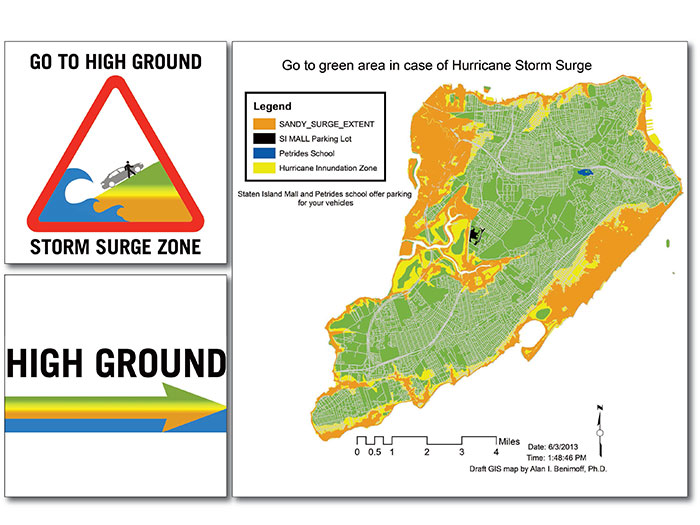

5. Above all, we need to educate people, that in storm surges when the water starts to rise, it is too late to escape. Climb to safety! Never take shelter in a basement that could fill with water and trap victims in seconds, but head to high ground.

Evacuation orders must be taken seriously in order to avoid loss of life, and government officials should be mindful of evacuation plans for people with disabilities, the ill, the elderly, and people in hospice and home care.

Education can also guide appropriate building codes and construction styles when decisions are made to rebuild. Appropriate low-cost ADA-compliant signage should guide residents to high ground, and let residents know the vulnerability of their location.

Local officials should also designate areas on high ground where residents can move their vehicles to protect them from the storm.

I am confident that if we continue to have this “serious conversation,” we have many options and a bright future. Although we are extremely vulnerable, we are much more fortunate than many coastal cities in that we have a lot of high safe ground. Let’s use it wisely.

Written by Dr. William J. Fritz, Interim President, College of Staten Island

William J. Fritz, PhD, is the interim president of the College of Staten Island, Willowbrook. He is also a professor of geology and a member of the earth and environmental sciences doctoral faculty at the CUNY Graduate Center. Dr. Fritz has authored “Roadside Geology of Yellowstone Country,” “Basics of Physical Stratigraphy and Sedimentology” and more than 50 scholarly publications. He presented “Storm Surge Model for New York, Connecticut, and Northern Waters of New Jersey with Special Emphasis on New York Harbor” at the 2012 Geological Society of America’s annual meeting and exposition in Charlotte, N.C., a report written in June 2012 and presented the week after Sandy hit New York City. He also hosted the forum “Superstorm Sandy: A Serious Conversation About the Future of Staten Island” at the College of Staten Island, where a diverse group of professionals provided members of the CSI and Staten Island communities with information on the superstorm and how to prepare for future severe weather events.

This story originally appeared in the Staten Island Advance October 27, 2013 and is © 2013 SILive.com and reprinted here with permission.