Commuters on Staten Island are too well aware of the nightmare that it can be to get from one place to the other in the borough.

Congestion, poorly designed or outdated routes, and a severe lack of public transportation leave thousands of people stressed, angry, and frustrated on a daily basis. In addition, thousands of cars sitting idle in traffic jams contribute to the air pollution problem in the area.

However, crucial research being conducted at the College of Staten Island is seeking an end to these woes.

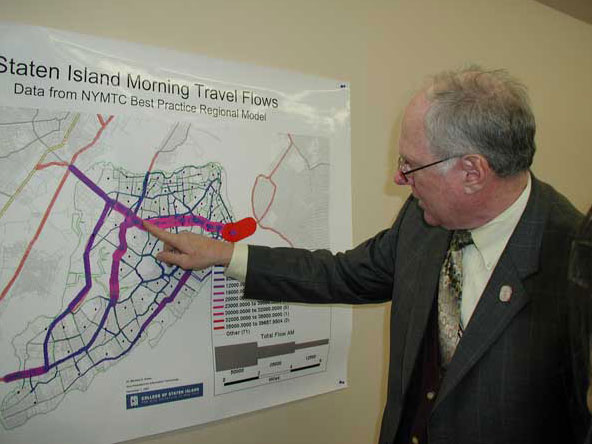

At present, there are two methods of examining traffic flow patterns. One is the Travel Demand Model that employs usage maps generated by organizations such as the New York Metropolitan Transportation Council, showing the average volume on Island roadways at certain parts of the day.

Another approach to the problem is computer simulations, like those currently used by Michael Kress, CSI Vice President for Technology Systems, and Jonathan Peters, an associate professor of finance at the College.

Outerbridge Issues

Thus far, Kress and Peters have constructed an accurate simulation of a key bottleneck area that plagues commuters to and from Staten Island—the Outerbridge Crossing. These simulations allow the researchers to put potential remedies in place without further inconveniencing commuters, if the method turns out to be faulty.

Click here to view a real-world computer simulation (in Windows Media format) of the Outerbridge Toll Plaza with only one cash lane open. EZPass tag holders are featured in yellow.

Noting that lanes on the bridge are only ten feet wide, as opposed to the average width of 12 feet, Peters says that this results in severely reduced traffic flow over the bridge during peak times, and especially during the holidays. On an ordinary day, according to Peters, the bridge experiences a high volume of vehicles, compounded by the narrow lanes.

On a holiday, such as last Christmas Eve, when a 13-mile back-up ensued at the bridge, leading all the way out to the Driscoll Bridge in New Jersey, the situation is much worse, due to an even higher capacity of commuters and more people using the cash lanes at the toll plaza. These problems have only become worse due to the improvements to the Driscoll Bridge, which are resulting in increased traffic from the Garden State Parkway and Routes 35/9.

Peters and Kress report that the simulation research that they’ve conducted on the Outerbridge Crossing indicates that the Port Authority of NY and NJ, which administers the bridge, should keep all toll lanes open at all times to encourage the flow of traffic through the toll plaza, and avoid back-ups.

Pointing to a 1987 report published in an international traffic engineering journal, which called the bridge functionally obsolete, Peters stresses that “just by operating the bridge differently, you should have less delay.”

Having found one way to ease problems at one traffic hotspot, Kress and Peters are also in the process of creating a simulation of the major roads and highways, as well as some minor roads, in the borough to pinpoint other difficult areas for commuters.

At this point, this simulation is in the test stage to see how traffic flows on various thoroughfares, but the two researchers hope eventually to have a model that is as accurate as their Outerbridge Crossing simulation.

So far, Kress states that “what we are learning from our models is that our system is at capacity.”

How Can Staten Island Overcome These Problems?

Kress emphasizes that simple road improvements, like the addition of right-hand passing lanes at intersections where vehicles turning left block traffic, adjusting the geometry of some streets, or adding new roads can alleviate some of the problems.

Peters adds that with the region’s growing population, drastic improvements in mass transit are also crucial to give people other opportunities than driving their cars. The problem in this respect, according to Peters, is a lack of government funding.

Peters says that Staten Island takes in enough money annually from tolls to easily finance much-needed improvements to the commuter infrastructure, and considerably reduce its myriad traffic woes, but all of the money collected obviously does not go just to this borough.

With that problem in mind, Kress and Peters note that, beyond the benefits of simulations mentioned above, these models lend authority to their research and strengthen their appeals to government officials for solutions and improvements to the network of roads on Staten Island.

With a slightly ominous tone, Peters stressed, “If the United States can’t solve [traffic issues on] Staten Island, we will have huge problems” on a nation-wide basis. With their simulations, and other studies, they might just help to answer some very important questions.

![[video] UNICEF Honors CSI Students for creating “A Bridge to Clean Water” for Children in Kenya](https://csitoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Lyons-Lab-Web.jpg)